Seven days of Halloween – day four!

“On the fourth day of Halloween my true love sent to me four soulers souling, three nuts a cracking, two cats a mewing and a vampire in a coffin.”

Day four in our countdown to October 31st (which takes its inspiration from the Twelve Days of Christmas song for some reason!) Previous days can be read here: https://museumofwitchcraftandmagic.co.uk/news/seven-days-of-halloween-day-three/

Four soulers souling

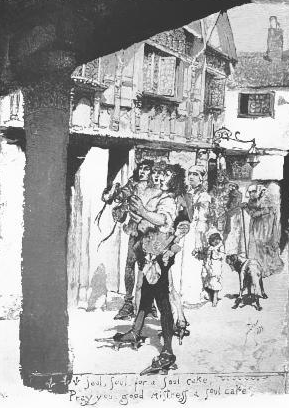

“A soule cake, a soule cake, Have mercy on all Christen soules for a soule-cake.” Written down by John Aubrey in the 1600s.

A soul cake is round, decorated with a cross and made with spices and currents. People used to go from house to house asking for a soul cake. For each cake received, a prayer was meant to be said for the dead. In Wales, this custom is known as “collecting food for the messenger of the dead.” The custom seems to date from the Middle Ages. In some parts of Britain people go “souling” which involves putting on a play and singing songs. Connections have been suggested between this practice and modern day trick or treating.

There are numerous versions of the Soul Cake songs, here are two examples:

Song 1: “For we are all poor people,

Well known to you before.

So give us a cake for charity’s sake,

And our blessing we leave at the door.”

Song 2: “Soul day, Soul day,

We be come a souling.

Pray good people remember the poor,

And give us a soul cake.

One for Peter, two for Paul,

Three for him that made us all

An apple, a pear, a plum or cherry

Or any good thing to make us merry.

Soul day, Soul day,

We have been praying for the soul departed.

So pray good people give us a cake

For we are all poor people,

Well known to you before,

So give us a cake for charity’s sake,

And our blessing we’ll leave at your door.”

Recipes can be found online, Peter Hewitt (Museum manager) made some last year. See https://museumofwitchcraftandmagic.co.uk/news/cakes-and-ale/ for a recipe.

There are lots of other foods for Halloween which relate to ideas about death. In Brittany,people leave pancakes and cider out for the spirits of the dead on October 31st. They are often left in cemeteries.

“Pan de muerto” or Bread of the Dead/Dead Bread. Made in Spain and Mexico to eat during the festival of Hallowtide (or in Mexico the Day of the Dead). The sweet bread is decorated with two crossed bones.

A traditional Hallowtide food in Italy are “fave dei morte” or beans of the dead. The association of beans and death may date back to classical times, as beans were scattered on coffins in Italy as an offering to the Gods of the Underworld.

“Huesos des santos” or bones of the holy/Saint’s bones. These cakes are made and eaten in Spain on October 31st.

And of course, sugar skulls made in Mexico to celebrate “Dia de los Muertos” or The Day of the Dead.

This Mexican festival begins on October 31st and ends on November 2nd. It therefore coincides with the Medieval Hallowtide period.

The festival is similar to Halloween in many ways:

- They take place at the same time of year

- They are both European festivals that have been adopted and enhanced in the Americas

- There seems to be a fusion of Christian and pre-Christian belief in both festivals. The Day of the Dead blends Aztec ideas with Spanish Christian ones while some argue that Halloween derives from the pagan festival of Samhain.

- There is a lot of food in both festivals.

- People wear masks and have revels in both festivals.

However the tone of the festivals are significantly different and so is the attitude towards death.

The Mexican festival is still very much a religious festival whereas most people’s celebration of Halloween is not connected with religion. The Day of the Dead is about the acceptance of death, it is mocked but it is not feared.

Halloween has come to be seen as a time of monsters and horror movies. It is more about fear and shock than acceptance of death as a natural part of life so in its modern incarnation, it is fundamentally different to the Day of the Dead.

The majority of these foods date from the Middle Ages and are Catholic Christian in origin. The Middle Ages was the time when the word Halloween came to be used.

The word Halloween means Holy Evening

Hallow (meaning holy, sacred in Old English)

+

Evening (which was shortened over the years to even then to e’en then to een to make the word Halloween)

=Hallow evening then Halloweven then Hallowe’en and now Halloween

To be accurate, one should really talk of Hallowtide (holy time). Halloween has become torn asunder from the other days that gave it is character, they are:

All Saints or All Hallows Day November 1st

All Souls Day November 2nd

These three days (October 31st, November 1st and 2nd) originally made up a three day festival.

The following text is taken from the timeline in our exhibition examining the development of Halloween. This section considers Halloween in the Medieval period.

A Church Festival – Halloween in the Middle Ages

“It was customary in former times, on this day, for persons dressed in black to traverse the streets, ringing a dismal-toned bell at every corner, and calling on the inhabitants to remember the souls suffering penance in purgatory, and to join in prayer for their liberation and repose.” Chamber’s Book of Days

In the early Middle Ages, the Church finalised the details of its calendar or liturgical year. As the Church spread across Europe, there was greater uniformity of practice and many celebrations moved around a great deal in these years. Eventually, October 31st, November 1st and November 2nd became a three day Church festival known as Hallowtide.

During Hallowtide, people seem to have visited Church thought about the dead and especially those who had passed into Purgatory (the place between Heaven and Hell where souls were burned to purify them of certain sins to prepare them for Heaven).

KEY DATE: By 1006, the three day Church festival of Hallowtide had been officially recognised across Europe.

In 609AD, Pope Bonifacee endorsed a feast known as All Saints. It was to be held in May and was intended to remember all those who had died for Christianity (the Saints and martyrs).

In 800AD churches in England and Germany were found to be celebrating the Feast of All Saints on November 1st. Eventually this became common practice across Europe and November 1st became All Saints Day. A time to remember the Saints and also to appeal for their help (especially their help or intercession for those who were dead and believed to be in Purgatory).

In 998AD Odilo, abbot of Cluny Abbey, heard voices from a cave which he believed to be the sound of souls in torment in Purgatory. He ordered a solemn mass for the souls of all Christian dead in his monastery. The date chosen was February and it was given the name All Souls Day — a day to pray for all souls.

1006 The feast of All Souls was officially recognised as a Church holiday to be held on 2nd November “which not only suited the sombre nature of the season but could be conveniently linked to the preceding festival, as saints were increasingly seen as intercessors upon behalf of departed souls…” Ronald Hutton, Stations of the Sun

Some examples of Hallowtide practices

“In Naples, All Soul’s Day was the focus of a particularly macabre ritual. The charnel houses were thrown open and lighted up with flowers, while crowds thronged through the vaults to visit the bodies of their friends of relatives, the fleshless skeletons of which were dressed up in robes and arranged in niches along the walls.” From Chamber’s Book of Days

1470s The Mayor of Bristol was expected to entertain the whole council and other prominent citizens and gentry to fires and drinks with spiced cakebread and sundry wines before they dispersed to their respective parish churches for evensong.

1517 Churchwarden’s accounts in Heybridge, Wessex record payments to Andrew Elyott and John Gidney of Maldon to repair the “bell knappelle” and rope for “Hallowmasse” suggesting the importance of bell ringing at this time of year.

1539 The records of St Mary of Woolnoth indicate that they paid five maidens in garlands to pay harps in the Church by lamplight.

Shakespeare mentions Halloween in his play The Two Gentlemen of Verona (1594). The lovesick Valentine is described by his clownish servant as “to speak puling like a beggar at Hallowmas.” This means that he speaks in a whining tone and demonstrates that begging rituals were associated with October 31st at this time.

1598 “These Lords (of misrule), beginning their rule at Allhallond Eve, continued…until Candlemas Day: in which space there were fine and subtle disguisings, masks, and mummeries.” John Stow, A Survey of London

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.